Such a treasure we have here in Los Angeles with the incredibly talented food critic, Jonathan Gold. Reporting for the Los Angeles Times, he has produced his latest 'list', along with a very cool interactive map. Check out Jonathan Gold's 101 Best Restaurants. Download, embed, bookmark this page! Do whatever you need to do to have this on hand. It is a must for any foodie. My favorite Los Angeles restaurant, Providence, receives the #1 position. If you happen to not have a subscription to the Los Angeles Times, you may not be able to catch the link. Never fear, scroll down below for the list.

Check out Jonathan Gold's 101 Best Restaurants on latimes.com

101

Apple Pan

(Susan Gerbic)

One of L.A.'s greatest culinary legacies is the California

lunchroom burger, the multi-layered composition of iceberg lettuce,

pickles and slightly underripe tomatoes, neatly arranged and slicked

with a sweet, thick dressing on a lightly toasted bun. The thin,

slightly charred beef patty becomes basically another texture in this

sandwich, more valuable for its crunch and it savoryness than for its

juice. The lunchroom burger is essentially a short-form essay on

crispness. When you want the mediocre version of this, you get a Big

Mac. When you are seeking greatness, turn to the Apple Pan, a homey

1940s institution imitated everywhere from Duluth to Bahrain. No matter

how many waiting people may be crowded in behind you, the countermen

will always draw you another cup of coffee from the gas-fired urn.

100

Dae Bok

(John H. Kim)

If you have contemplated a meal of blowfish, your dreams were

probably shaped by the popular conception of fugu, the notorious fish

of death. In Japan, fugu chefs are specially certified, and expensive.

Exquisitely orchestrated fugu meals often last hours. The Korean

conception of blowfish, on the other hand, is as the centerpiece of a

pleasant evening of alcohol and conversation, sipping black-raspberry

wine around a communal tabletop caldron of brick-red broth and

vegetables, slipping meaty pieces of simmered blowfish from their

curious V-shaped bones. Cooked as a jiri, soupy stew, blowfish may

remind you a bit of the texture of frog's legs. When you're almost

finished, the waitress reappears to mix the dregs of the pot with rice,

chopped vegetables and a little oil, and leaves it to fry into a

crisp-bottomed porridge of joy.

99

Comme Ça

(Ringo H.W. Chiu / For The Times)

Why doesn't Los Angeles have brasseries? We do, actually,

except they call themselves gastropubs and serve kale salad and

pan-roasted Brussels sprouts instead of giant crocks of choucroûte.

Sauerkraut has never done well here in the land of Meyer lemons and

year-round asparagus. But still, Comme Ça is more or less a brasserie in

the classic sense, with plateaux of chilled seafood, escargots

persillade and crisp sautéed skate Grenoblois, except that you can also

get a nicely turned Aviation No. 1 if you want — this is where the L.A.

cocktailian thing kicked off a few years ago — and the bloody-rare

cheeseburger is profound. The obsessions of owner David Myers run more

toward Japan than toward boeuf bourguignon these days, and the sleek,

theatrically lighted dining room may be a bit less chic than it used to

be, but when you're in the mood for steak frites, frisee aux lardons or

an oozing, cheese-intensive onion soup, Comme Ça is where you want to

be.

98

Fab Hot Dogs

(Sherrie Gulmahamad)

We may not have the Coney joints you see on every block in

some Detroit neighborhoods, the number of stands you see in Chicago, nor

the concentration of street vendors you see in New York, but Los

Angeles really is a hot dog town. Look at the enormous lines outside

Pink's, Dog Haus or the vendors who materialize outside nightclubs at 2

a.m. Or better, stop by Fab's, Joe Fabrocini and Susie Speck Mayor's

fragrant museum of the hot dog arts, where you can admire not just

standard dogs but Carolina-style slaw dogs, Italian dogs from northern

New Jersey, rippers and cremators, Hatch chile dogs and a close

facsimile of both Oki Dogs and the street cart dogs sold in New York's

Central Park — made, like everything here, with the artisanal,

natural-skin, small-production franks that Fab's imports from New

Jersey. Do you require tater tots with your franks? Say no more.

97

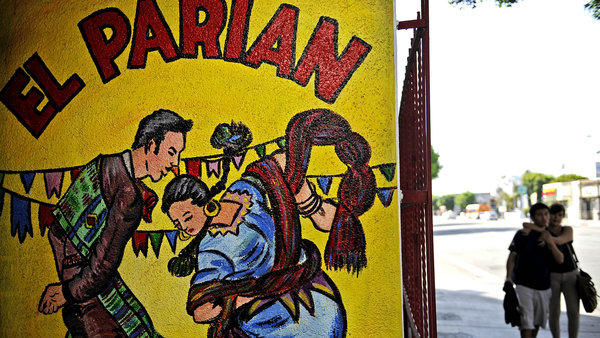

El Parian

(Mariah Tauger / For The Times)

The first Counter Intelligence column I ever wrote for The

Times was of El Parian, a lunch hall just west of downtown famous for

its Guadalajara-style birria: roasted kid hacked into chunks and served

in a strong consommé that tasted like amplified pan drippings. When the

waitress came to take your order, she didn't ask you what dish you

wanted, she asked you whether you wanted a full order or just half —

crunchy parts, stewy parts, tiny ribs, parts that look as if they come

from a joint of beef. With a basket of freshly patted corn tortillas and

a Modelo served so cold ice crystals sometimes form on the surface of

the beer, primal Mexican food doesn't get any better than this.

96

Ciro's

(Patrick T. Fallon / For The Times)

You could have any number of tequila-powered arguments about

which restaurant and which dishes best represent old-school East L.A.:

the giant burritos at El Tepeyac or the bean-and-cheese at Al and Bea's;

the grilled meat at La Parrilla or the tamales and carnitas at Los 5

Puntos. But for me, it always comes down to the iron-barred, split-level

dining room of this East L.A. institution, where the chile verde tastes

like a trip to grandmother's house, the enchiladas are first-rate and

the tiny flautas, the house specialty, are tightly rolled and very

crisp, buried under layers of chile sauce, thick guacamole and tart

Mexican sour cream. When I am trapped in an airless restaurant that

charges $150 for its tasting menu, my thoughts tend to wander toward the

juicy avocado salsa that Ciro's brings out free.

95

Nickel Diner

(Anne Cusack / Los Angeles Times)

The last time I visited the Nickel, musicians were playing

outside on the sidewalk; all banjo, slap bass and tight bluegrass

harmonies. From inside the restaurant, where I was contemplating a plate

of pulled-pork hash and a mug of black coffee, it was impossible to

tell whether the band was Mumford & Sons or a band that sounded like

Mumford & Sons, whether they were spare-changing or filming a

video, and whether they were sanctioned by the restaurant, a fragrant

diner on a block still dominated by flophouses, or whether they just

found it a convenient place to busk. In a neighborhood transitioning

from a skid row past to a luxury loft future, Nickel Diner is an

institution that respects both worlds. Proprietors Monica May and

Kristen Trattner seem to know everybody on the street, from the artists

to the homeless guys in rehab. The menu includes the pancakes, fried

eggs and bacon without which there would be rebellion in the streets,

but Nickel Diner also bakes its own bread, prepares elaborate cakes and

maple-bacon doughnuts, and makes delicious fried catfish with corn

cakes. The lunch crowd may come for the Lowrider Burger, but they don't

seem to mind the candied pecans in the chicken salad.

94

Kobawoo

(Cathy Chaplin / GastronomyBlog.com)

In Koreatown, a novice soon learns, most decent restaurants

specialize in a dish or two. You go to one place for grilled clams,

another for pork belly and a third for barbecued duck. Kobawoo, a

polished, destination restaurant in the inevitable mini-mall, is a great

place to go for crisp seafood pancakes, game hen stuffed with ginseng

and sticky rice, and pig's feet pressed into a cool, gelatinous terrine.

The home-style pindaeduk, mung-bean pancakes, are a big draw — the

pancakes are ethereal beneath their thin veneer of crunch, melting away

almost instantly in the mouth like a sort of intriguingly flavored

polenta. But Kobawoo is most famous for its version of bossam: boiled

pork belly you wrap up into leaves with raw garlic, sliced chiles and a

salty condiment made from tiny fermented fish. Bossam, a fabulous dish,

may sound more compelling after somebody presses a glass of cold soju

into your hands.

93

Bulgarini Gelato

(Stefano Paltera / For The Times)

It's not quite like going to visit the mad scientist in his

mountain lair, but a trip to Bulgarini, on an Altadena hill so steep

that Henry Ford once used it to test the engines of his new cars, can

sometimes feel pretty close. You've never been to a shop quite like

Bulgarini, dominated by a massive old espresso machine and decorated

with obscure homages to the AS Roma soccer team, and you've probably

never tasted gelato like Bulgarini's: pistachio flavored with nuts

hand-carried back from the Sicilian pistachio village Bronte; rich

goat's milk gelato spiked with roasted cacao nibs; apricot sorbetto that

captures the elusive, almondy essence of the fruit; or bitter, intense

gelato made with salted Florentine chocolate. House policy at Bulgarini

mandates a three-scoop minimum, at $2.50 per.

92

Cacao

(Cacao Mexicatessen)

Cacao, it must be said, has a fairly open mind on what might

go into a taco, so if you're one of those guys who feels options should

be limited to carne asada, chicken and pork al pastor, the restaurant

probably isn't for you. They make carnitas out of duck, for one thing,

neatly splitting the difference between the classic Mexican preparation

and French duck confit, and sometimes they make chicharrones out of duck

cracklings just to mess with your mind. Sea urchin has found its way

into the tacos, as have hibiscus flowers, huitlacoche and the occasional

suckling pig. Cacao expanded a bit and finally got its beer and wine

license, so you can make an evening out of it if you're so inclined.

Cacao is a neighborhood restaurant in a fairly gentrified neighborhood.

But if suffering good coffee, folksy music and the bourgeois presence of

duck is the price one has to pay for access to Cacao's fig mole,

vegetarian-friendly menu and mushroom-stuffed chiles rellenos, sometimes

sacrifices have to be made.

91

Sapp Coffee Shop

(Julian Fang)

Sapp, which features neither regional cooking nor dizzyingly

late hours, may not be the sexiest restaurant in Thai Town. You will

find neither wild boar nor sataw beans; cassia buds nor crispy pork. But

for decades now, Sapp has been perhaps the most dependable lunchroom in

Hollywood, cheery on the drizzliest day, with clove-scented roast duck

noodles, great Isaan-style grilled chicken, a version of the

pig's-ear-enhanced pork salad nam sod that is as sparkly in flavor as it

is gray in appearance. Boat noodle soup has become almost a religion in

Thai Town, with a half-dozen places claiming superior authenticity, but

Sapp's version is magnificent: a musky, blood-thickened beef soup

screaming with chile heat; tart lime juice in lockstep with the

funkiness of the broth.

90

Krua Thai

(Lawrence K. Ho / Los Angeles Times)

If it's 2 in the morning and you're eating noodles in North

Hollywood, chances are pretty good that you have washed up at Krua Thai,

where the smoothies are banging, the Barbie-box-pink yen ta fo noodles

are properly stinky and the wide, slippery pad kee mao have enough of a

fresh-chile sting to help you forget the earlier evening woes. Pad Thai

may be a dish a lot of us got tired of when Duran Duran was still on the

charts, but the ultra-spicy, tamarind-soured, fish-sauce-laced

house-special version here is about as good as it gets, a powerful dish,

truly exotic, sweet and squiggly and delicious, stocked with both tofu

and big shrimp — the dish made vivid again after 30 years as a cliché.

89

Mo-Chica

(Gary Friedman / Los Angeles Times)

If you want a pisco sour, you're in the right place: The

foamy, tart, lightly bitter version of the Peruvian national cocktail

flows like water. Ricardo Zarate is a chef's chef, so you will find

artfully deconstructed versions of Peruvian dishes like papas a la

Huancaina, which is presented as a bacon-wrapped terrine of neat potato

slices lightly drizzled with the traditional sauce of cheese and

amarillo chile; or the Chinese-Peruvian stir-fry lomo saltado,

reinvented as a construction of sautéed tomatoes, onions and sliced

filet mignon supporting a Lincoln Log superstructure of stacked French

fries. Zarate's original Mo-Chica was everyone's feel-good restaurant

story for a while, a popularly priced lunch counter in a community-owned

market that just happened to serve the best Peruvian food in town —

ceviche and tiradito with all the rustic flavor of Lima but using

sushi-bar-quality fish. So as good as this sleekly modern Mo-Chica may

be, and as skillfully as Zarate translates Peruvian classics into bar

snacks, its success may be bittersweet.

88

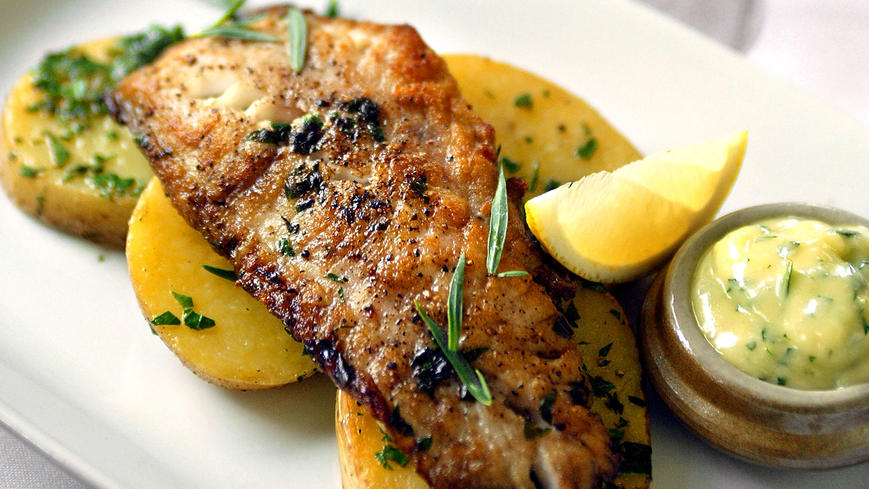

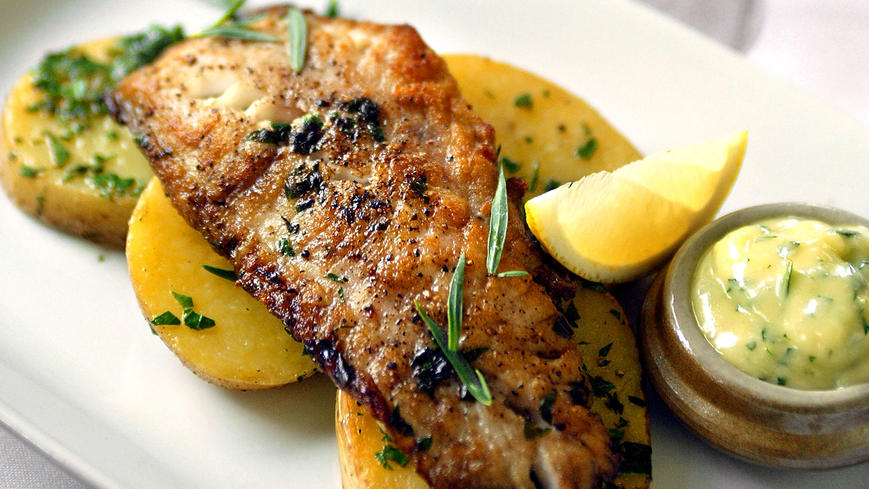

Musso & Frank

(Jay L. Clendenin / Los Angeles Times)

Musso's, if you look at it a certain way, is a living museum

of 1920s American cuisine: the avocado cocktails, crab Louie, jellied

consommé, grilled lamb kidneys and Wednesday sauerbraten that William

Faulkner and Charlie Chaplin used to enjoy, presumably after they had

lubricated their insides with gin. If you grew up in Hollywood, the

waiters are likely the same ones who used to bring you flannel cakes

when you were a kid. Mixology has made great strides in the last 94

years, but Manny is still the guy you want making your martini. And

although you can undoubtedly find more dependable steaks and chops and

sautéed petrale sole in Los Angeles now, it always feels like a

privilege to slide into one of the booths underneath the faded mural and

contemplate your first bourbon of the evening.

87

Rocio's Mole de los Dioses

(Ricardo DeAratanha / Los Angeles Times)

L.A.'s best mole may be a subject for debate, and the

conflict between regional styles will never be resolved, but there is no

doubt that Rocio Camacho makes more kinds of mole than anybody else in

town — not just the seven traditional moles of Oaxaca or moles from

Puebla or the Distrito Federal, but versions based on almonds or

hibiscus blossoms, tamarind or coffee, tequila or pistachio nuts. Get

the mole sampler and spend the evening comparing her Oaxacan black mole

with her mellower mole Poblano; with the spicy, smoky mancha manteles;

or with her signature mole de los dioses, which has a funky, toasty hint

of the corn fungus huitlacoche. Is the sauce of cactus and sunflower

seeds technically a mole at all? We will leave that for the scholars to

decide.

86

Patina

(Anne Cusack / Los Angeles Times)

You pull up in front of Walt Disney Concert Hall, in the

manner you have seen in so many car commercials. You walk into the

intimate whale-ribbed dining room carved out of the Frank Gehry

structure and are led to an ironed white tablecloth set with heavy

silver. The thick wine list is rich in hidden treasures if you are

willing to consider Corbières or Slovenian Pinot Gris instead of Napa

Chardonnay. And then your first course is set down in front of you, a

mosaic of a dozen or more kinds of turned seasonal vegetables, set

upright in rows that may remind you of ranks of chessmen, each cooked in

its own little pot before final assembly, then glazed with a reduction

of the combined juices. It is a lot of work, this mosaic — you are not

going to be replicating it at home. It reminds you that you are in a

grand restaurant celebrating big things, that you are in an

agriculturally abundant part of California and that it is possible to be

festive without resorting to oversized hunks of meat. Does it matter

that some of the vegetables are overcooked, that the pink sauce is

without flavor and that you wish somebody had thought to add a few snips

of tarragon, a scattering of Maldon salt, a touch of citrus zest —

anything that might possibly transform the dish into something alive?

Perhaps not. The occasion has been noted.

85

Newport Tan Cang Seafood

(Cathy Chaplin / GastronomyBlog.com)

When friends stagger back from the San Gabriel Valley

mumbling of lobster, lips numb with chile and their hearts filled with

glee, they have almost certainly just come from this converted Marie

Callender's, where even strong men are defeated by the parade of sautéed

pea shoots with garlic, crunchy salt-and-pepper squid and then the

gargantuan house-special lobster, five pounds or more, fried with heaps

of chile, black pepper and chopped scallion, enough to haunt your

fingernails for days. What Newport serves is Southeast Asian-inflected

Cantonese food, kind of Chiu Chow but kind of not, although as far as I

can tell, the Cambodian-born owners haven't quite figured it out either.

84

Mayura

(Jay L. Clendenin / Los Angeles Times)

Mayura, in a strip mall a block or two north of Culver City's

studio district, may be the last place in Los Angeles you would expect

to find a restaurant specializing in the cooking of Kerala, a region on

south India's Spice Coast. Even if you have eaten in other local

southern Indian restaurants, a lot of the food may be new to you:

saucer-shaped rice-flour saucers called appam; an obscurely flavored

fish curry with undernotes of tamarind and garlic; the peppery, buttery

cashew-rice dish ven pongal; or even avial, a Kerala-style dish of

julienne vegetables sautéed with coconut, as useful as a condiment as it

is satisfying as a main dish. Mayura, oddly enough, also functions as a

halal Indian restaurant, with a separate kitchen dedicated to cooking

meat (and no alcohol). It's not the best food in the house, but you can

get the usual plates of chicken tikka and vindaloo as well as Pakistani

dishes like haleem and nehari, which seems to both confuse and satisfy

the Muslim and Hindu clientele.

83

Ración

(Katie Falkenberg / Los Angeles Times)

We are all becoming comfortable with the idea of San

Sebastian as one of the great food cities of the world, a smallish

Spanish metropolis with a freakish concentration of Europe's best

restaurants and bars that are the answer to a tapas-lover's sweatiest

dream. Ración, run by Border Grill vets Loretta Peng and Teresa Montano,

is no Arzak, but it is a nice place to drop in for a glass of Txakolina

or Basque cider and a supper of Basque-inspired tapas: crisp, gooey

chicken croquettes; lamb meatballs glazed with caramelized tomato sauce;

tiny squid stuffed with duck sausage; Spanish cured meats; or pintxos

of sliced tongue with pickled shallots. The food is inspired by rather

than duplicative of Spanish cooking.

82

101 Noodle Express

(Cathy Chaplin / GastronomyBlog.com)

Beef roll? Did somebody say beef roll? Because while

millenniums of gourmands may consider Shandong to be the heartland of

Chinese haute cuisine, nearly everybody at 101 Noodle Express dives past

the pumpkin-shrimp dumplings, the hand-torn noodles and the famous

Dezhou chicken right to that brawny, steroidal composition of crisp,

flaky Chinese pancakes with cilantro and sweet, house-made bean sauce

rolled around fistfuls of long-braised beef. Are these Chinese burritos

as unwieldy as edible softball bats? Probably. But a meal at 101 Noodle

without a beef roll is as unthinkable as a visit to Lawry's without

prime rib.

81

Mantee

(Lawrence K. Ho / Los Angeles Times)

Southern California is home to a lot of Lebanese-Armenian

restaurants, most of which serve satisfying versions of raw kibbeh,

fattoush salad and other classics of the Middle Eastern table. But

Mantee, which is run by Jonathan Darakjian, a chef whose family owns one

of the best Armenian restaurants in Beirut, brings a different kind of

edge to the cuisine, so the flaky pastry called borek oozes cheese when

you prod it with a fork, prosaic baked feta is transformed into a kind

of Armenian queso fundido and the namesake dish, a superheated platter

of tiny beef dumplings sizzling in a bath of garlicky yogurt, is grand.

The kebabs are no different from what you'll find in any other Middle

Eastern restaurant, but if you're in the mood, the peppery soujak

sausages will be brought to you aflame.

80

Mariscos Jalisco

(Mariah Tauger / For The Times)

If you have been to a street-food competition in Los Angeles,

and there have been quite a few over the last few years, you have

witnessed the coronation of the Mariscos Jalisco truck, which wins these

things so frequently that it should probably just accept a lifetime

achievement award and hang it up. Raul Ortega and his signature tacos

dorados de camaron, fried tacos with shrimp, are just too formidable. If

life were just, Ortega would be a wealthy man, and you would see his

face plastered on airport concessions, glossy chain restaurants and

cerveza ads. So it is sometimes surprising to roll up to his battered

truck, parked in the same location for more than a decade, and have him

personally hand you a taco, ask if you might want to try a plate of

ceviche or aguachile and gesture toward a spot on a low wall where you

might sit and eat. You crunch into one, the fiery salsa runs down your

chin and you are content.

79

Border Grill

(Mark Boster / Los Angeles Times)

Twenty-five years on, Border Grill may be less a restaurant

than it is an institution, the photogenic face of 1980s Mexican cuisine

sustained into another age. A lot of Mexican chefs make their own

tortillas, compile encyclopedic tequila lists, serve sustainable seafood

and shop at the farmers market now. The most exciting Mexican cooking

here now is regional, featuring the dishes of a single town. Mary Sue

Milliken and Susan Feniger, as their critics point out, are no more

Mexican than Ori Menashe is Italian or Jordan Kahn is Vietnamese. But

while they aren't redefining Mexican food, at least at this point, they

prepare it extremely well, transforming the taco, the tostada and the

homely enchilada into dishes almost unrecognizable to El Cholo

partisans; the charred skirt steak and the pescado Veracruzano have

crazy soul. Border Grill is the rare mainstream restaurant whose tacos

don't make you yearn for a truck parked by an auto-parts junkyard

somewhere in East L.A.

78

Chichen Itza

(Annie Wells / Los Angeles Times)

The first time I ate at Chichén Itzá, I booked a flight to

the Yucatan almost as soon as I got home. Because if the Yucatecan

cooking was this good at this restaurant stall in La Paloma, a

community-run marketplace just east of USC, I could only imagine how

delicious it might be in the place of its birth. The food in Mérida

turned out to be great, of course. But so is Chichén Itzá, named for the

vast temple complex north of Cancún, whose menu is a living,

habanero-intensive thesaurus of the panuchos and codzitos, sopa de lima

and papadzules, banana-leaf tamales and shark casseroles that make up

one of Mexico's spiciest cuisines. From the banana leaf-roasted pork

cochinito pibil to the cinnamon-scented bread pudding caballeros pobres,

the cooking of Gilberto Ceteno junior and senior is as fresh as a

marketplace restaurant in Mérida.

77

Meals by Genet

(Genaro Molina / Los Angeles Times)

Fairfax Avenue's Little Ethiopia district has grown denser

over the decades, and whether your taste runs toward the vegan, the

old-school incense-scented or full-on party cuisine, it has never been

easier to find a decent Ethiopian meal. But year after year, we find

ourselves returning to Genet Agonafer's bistro, a softly lighted dining

room whose gentle beef tibs, her crisp-skinned fried trout, her vegan

stews and her minced raw beef kitfo owe much to the virtues of careful

home cooking. And her dorowot, a two-day chicken stew vibrating with

what must be ginger and black pepper and bishop's weed and clove, may be

as rich and complex as a Oaxacan mole but cuts straight through to the

Ethiopian soul.

76

Hannosuke

(Kirk McKoy / Los Angeles Times)

In the rush to quantify báhn mì specialists and artisanal

gastropubs, we often overlook the Japanese supermarket food court, short

on amenities but frequented by customers who know how Japanese food is

supposed to taste. And if you are a strict empiricist, the sauce-brushed

tempura on the tendon, rice bowl with tempura, basically the only dish

here, may seem to lack the crispness and the featherweight crunch that

you might expect from a branch of a famous Tokyo tempura bar. But

Hannosuke's aesthetic takes hold in an instant. That slightly sogged-out

crunch — it's still really crunchy, expressive of the roasty, nutty

flavors of the expensive sesame oil used for frying, of the subtle

sweetness of prawns and Tokyo eel.

75

Corazon y Miel

(Ricardo DeAratanha / Los Angeles Times)

A young chef's recipe for success did not used to include

opening a tequila bar in Bell, a working-class suburb famous chiefly for

the corruption of some of its elected officials. It's a long haul from

the Westside for a fizzy shot of Ron Bull and a plate of roasted chicken

hearts with honey. But Eduardo Ruiz, who comes from the head-to-tail

wonderland of Animal up on Fairfax Avenue, is made of sterner stuff. And

his chefly interpretation of Mexican bar snacks — hot potato chips with

battleship-gray charred scallion dip; seared slices of carnitas terrine

with cubes of Coca-Cola gelee; pigskin two ways; knots of bacon and

roasted jalapeños with mayonnaisey corn salad — is at the vital edge of

Los Angeles cooking at the moment.

74

Attari

(Noms Not Bombs)

If you have ever asked an Iranian American where to have

dinner out on the Westwood Tehrangeles strip, she will probably mumble

the name of one kebab house or another, followed by a plea to come eat

at her mother's house instead. But lunch? That's easy. The leafy patio

of Attari is a bit of pre-revolutionary Tehran cafe society transplanted

into a sleepy office courtyard, all Chanel handbags, exquisitely

tailored clothing and rituals of decorum that rival anything out of an

Ernst Lubitsch film. Attari is the house of osh, the nourishing Iranian

soup that was, in the restaurant's first year, the only dish on its

menu. Now everyone is here for mashed eggplant with yogurt, chopped

salad and Attari's sandwiches: lengths of toasted French bread dressed

with fresh tomatoes, lettuce and a smattering of spiced, super-tart

Iranian pickles. Get the sandwich stuffed with kuku, a vivid-green

frittata that breathes the essence of fresh spring herbs. On Fridays,

abgoosht is the mandatory order, an intricate stew of lamb and grains

mashed into a thick, homogeneous paste with the texture of refried beans

(its expressed essence is served separately as soup).

73

Golden Deli

(Golden Deli Group)

Is there better pho? Perhaps. Pho Thanh Lich in Westminster

has better noodles, and the broth at Pho Filet in South El Monte has

more flavor. Are there better spring rolls? Doubtful, although the ones

at Brodard in Garden Grove are pretty good. But Golden Deli has been the

default Vietnamese noodle shop in the San Gabriel Valley for more than

30 years, a cramped, eternally crowded storefront whose clones now have

clones, where the pho and especially the crackly fried spring rolls

called cha gio have always been worth the discomfort. The prospect of

Golden Deli's bun thit, noodles tossed with fish sauce, grilled pork and

fresh herbs, is always a happy one.

72

Sqirl

(Irfan Khan / Los Angeles Times)

This was a year when the ideas of craft and homespun virtue

crashed over the land like a sticky wave of artisanally gathered honey,

and pop heroes began to include micro-distillers and baconistas as well

as actors and banjo players. Making great preserves from superb

California fruit is not a new idea, but Jessica Koslow, a former

world-class figure skater, is very good at it, and her tiny, East

Hollywood cafe exists to reanimate the flavors she preserves: rice

porridge with toasted hazelnuts and jam; rice tossed with tart sorrel

pesto and preserved lemon; fried eggs with puréed tomatillos and

house-fermented hot sauce; or even the astonishing "Hamembert" plate

with Mangalitsa ham, oozing wedges of Camembert cheese, and an artfully

charred length of baguette. Sqirl shares its minimalist premises with

the championship barista of G&B Coffee, if you care to linger on one

of the curbside packing crates that double as chairs with a perfectly

made cappuccino.

71

Little Dom's

(Robert Lachman / Los Angeles Times)

When you are a teenager in a land without meatball subs,

Little Dom's is what you think Italian restaurants are going to be like

when you grow up: faded dark-wood places with slouchy booths and dim

lighting and frosty highballs near to hand. Brandon Boudet, who also

runs Dominick's and Tom Bergin's, is a master at taking the unloveliest

aspects of Italian American food and elevating them into cuisine. Other

guys may debate the authenticity of chicken parm or spaghetti and

meatballs; Boudet makes good ones, not quite your grandmother's, but

close enough. To the casual eye, Little Dom's may resemble a South

Jersey joint, but Boudet is from New Orleans, and the place is modeled

on neighborhood Creole Italian places from that city, so along with the

burrata salad you get oyster po' boys, crawfish garnishing grilled fish,

and fried shrimp with artichokes. There are complicated Italian

American egg dishes for breakfast too.

70

Valentino

(Ricardo DeAratanha / Los Angeles Times)

If you're an old-school gourmand in Los Angeles, you probably

have a relationship with Valentino, which was the first restaurant here

to serve white truffles, balsamic vinegar or radicchio, the first to

fetishize great olive oil, the first as devoted to ancient Italian

vintages as the Le and La places were with Bordeaux. (I will never

forget my first taste of Quintarelli Amarone here, which is as close as I

had gotten to a sweet, musky taste of heaven.) Will you eat better if

you are known to the house? Certainly. This is among the last of the

great host-driven Italian restaurants, a place where some regulars have

never seen a menu and the waiter's job is to solidify your abstract

desire into fish and pasta and wine. Valentino is very expensive; the

wine bar within, serving some of the same food and a crack at the

spectacular wine list, is less so.

69

Hunan Mao

(Gina Ferazzi / Los Angeles Times)

There are nearly a dozen Hunan restaurants in the greater San

Gabriel Valley, and the best of them, including this one, tend to

specialize in the funkier side of the cuisine: the steamed and smoked

meats, the simmered organs, the fermented vegetables and the oily,

fearsomely hot dishes that make Hunan a paradise of peasant cuisine. The

house-smoked Hunan ham has the smoky punch of first-rate barbecue, at

its best coarsely chopped and sautéed with dried long beans, a handful

of garlic cloves, and the vivid red and green chopped chiles that

dominate almost everything here. Is the restaurant named for the

Hunan-born Chairman Mao? It is, and you should probably try its version

of "Mao's braised pork," a sweet, slightly spicy clay-potful of

thick-cut braised pork belly and garlic — almost unbearably rich, and

soft enough to collapse at the touch of a chopstick. Or just get a

steamed fish head and call it a day.

68

Grill on the Alley

(Gary Friedman / Los Angeles Times)

Everybody looks good at the Grill, which is as elegantly

lighted as a George Hurrell print. Everybody eats well there too — the

steaks are good; the martinis are perfect; the Caesar salad, the steak

tartare, and the corned-beef hash are sublime. It is the Beverly Hills

version of Musso & Frank, with show business moguls instead of set

designers, stars instead of character actors. Are the regulars eating

this delicious food or just pushing it around their plates? It's hard to

say. But assuming that you are eating, you will also find this town's

essential rice pudding: touched with cinnamon, drizzled with heavy

cream, coaxing the nutty, rounded essence out of every grain of rice.

67

Bierbeisl

(Anne Cusack / Los Angeles Times)

Los Angeles hadn't been lacking the flavors of Austria; not

exactly. Austrian-born chef Wolfgang Puck always kept the odd

kaiserschmarrn or bone-marrow soup on the menu at Spago, and

Austrian-born winemaker Manfred Krankl, back when he was the first

sommelier at Campanile, introduced the city to the strange and glorious

world of Austrian wines. Even Austrian-born ex-Gov. Arnold

Schwarzenegger ran an Austrian-influenced restaurant in Venice for a

while. But Bierbeisl, Bernhard Mairinger's emporium of schnitzel,

milk-poached weisswurst and creamy goulasch is a purely Austrian

restaurant of a sort we have never quite seen here, with a schnapps list

and blueberry kaiserschmarrn for dessert. Sausage tasting menus with

beer pairings? Be still my heart.

66

Gjelina

(Bob Chamberlin / Los Angeles Times)

It is a cool night, and you have made it past the throng at

the bar, and you are out on the patio at Gjelina, not far from the fire

pit, contemplating the wonder of a crisp little pizza with shaved

asparagus and egg. You may have worked your way through a few vegetables

— there are a lot of vegetables here — roasted beets with their tops,

perhaps, and there may be duck confit or a bean and barley stew yet to

come. Gjelina is cheerful, boozy and known for both its extremely

good-looking customers (a lot of young actors tend to show up here late)

and Travis Lett's decent organic-fetish Italian food. The scene may be

as crunchy as the wood-fired pizza crust, but relax: It's Abbot Kinney.

65

Coni's Seafood

(Mariah Tauger / For The Times)

Aficionados of Mexican seafood in Los Angeles have for years

been obsessed with the peregrinations of Mr. Sergio Peñuelas, the ronin

chef long associated with the Mariscos Chente chain. The restaurants

always had great shrimp dishes, supposedly made with seafood a member of

the family brought herself from Mazatlan a couple of times a week, but

Peñuelas is a master of pescado zarandeado, an elusive dish of marinated

snook cooked by shaking it over charcoal until the flesh caramelizes

but does not char. Pescado zarandeado is apparently a difficult art —

many Sinaloan or Nayarit-style kitchens in town attempt it but few

consistently do it well. All you really have to know is that

Coni'Seafood, not far from the Hollywood Park racetrack, seems to be

Peñuelas' permanent home and that you should probably try the fiery

shrimp ceviche called aguachile as well.

64

Plan Check

(Luis Sinco / Los Angeles Times)

Looking for the gearhead version of a modernist hamburger?

Check out Ernesto Uchimura's model, layered with ketchup leather, pickle

shavings, homemade American cheese scented with kombu seaweed, and a

microscopically thin layer of fried cheese, tucked into a bun sprinkled

with white specks that look like sesame seeds but crunch like breakfast

cereal. What you taste is salt, juice and the crunchy char of

well-cooked meat. The Plan Check Burger has been carefully engineered to

resemble the great bar burgers of your youth, and it re-creates them in

3-D, in Imax and with stereophonic Dolby sound. The French fries are

cooked in melted beef fat and gently dusted with smoked salt, and every

piece of fried chicken is the crunchiest. It's all very retro-futurist,

with a long list of Japanese whiskies to boot.

63

Langer's

(Gary Friedman / Los Angeles Times)

"I've always pushed the pastrami," the late Al Langer told me

once. "And you want to know why? Because it costs me a little less than

corned beef." But even after the great deli man's demise, the

institution he founded continues to serve the best pastrami sandwiches

in America, in a part of Los Angeles now better known for its pupusas

than for its knishes. The rye bread, double-baked and served hot, has a

hard, crunchy crust. The long-steamed pastrami, dense, hand-sliced and

nowhere near lean, has a firm, chewy consistency, a gentle flavor of

garlic and clove, and a clean edge of smokiness that can remind you of

the kinship between pastrami and Texas barbecue. Norm Langer, Al's son,

recommends the No. 19, with pastrami, swiss cheese and cole slaw. I like

my pastrami straight.

62

Cooks County

(Jay L. Clendenin / Los Angeles Times)

Daniel Mattern and Roxana Jullapat, Campanile veterans who

most recently were in charge of the kitchen at Ammo, operate in the

tradition of Los Angeles pan-Mediterranean cooking, sometimes called

urban rustic cuisine, although the occasional sharp North African edge

seems all their own. Mattern's cooking incorporates not just the seasons

but also the microseasons of Southern California produce — you can tell

the moment green garlic gives way to sweet spring onions by the garnish

on the steamed clams, and the people who come here tend to come here a

lot. Cooks County is a restaurant you could visit three times a week and

then come back for oxtail hash and cheese biscuits at Sunday brunch.

61

Bludso's

(Brian van der Brug / Los Angeles Times)

Kevin Bludso, as you probably know, is the muscle behind a

fancy new barbecue restaurant up on North La Brea Avenue that also

serves craft beers and the kind of cocktails fancied by mustachioed

dandies. But you might as well tool down to Compton when the urge for

barbecue strikes, because the brisket that issues from the battered

steel smokers behind Bludso's original restaurant is a paradigm of meat,

beef that disappears so quickly that if it weren't for the feeling of

satisfying fullness you might swear that you had less eaten it than

dreamed it.

60

Kang Ho-dong Baekjeong

(Mel Melcon / Los Angeles Times)

Kang Ho-dong is a former wrestler turned TV personality, like

a Korean Kim Kardashian in a singlet. Kang Ho-dong Baekjeong is the

local branch of a restaurant chain he runs on the side, a concrete

bunker of tabletop grills fitted into the Art Deco Chapman Market night

life complex. The restaurant has no sign in English but is easily

identified by the life-sized cardboard cutouts of Kang Ho-dong flanking

the entrance. On weekends, the wait for a table is often two hours. The

menu is short, basically a pamphlet listing various cuts of meat of

surprisingly high quality. Unless you have a specialist's agenda, you

will probably order one of the two beef set-course dinners, which

include the eggs and cheese corn that cook in special wells set into the

grill. The waiter will show you how to mix a soju bomb. Sobriety is not

considered a virtue here.

59

The Hungry Cat

(Liz O. Baylen / Los Angeles Times)

When soft-shell crabs come into season, the Pacific

langoustines are running or it is time to strap on the bibs and dive

into a dozen oysters or a pile of Maryland blues, the Hungry Cat,

Suzanne Goin and David Lentz's oddly shaped seafood restaurant, is

probably the first place to turn. Because the first rule of the kitchen

seems to be: Don't mess too much with the fish. That means the Santa

Barbara sea urchin isn't a source of intriguing richness, it's a sea

urchin, and the first-of-season Alaskan halibut may be served with

risotto, yellowfoot mushrooms and ramps, but it still looks and tastes

recognizably like a fillet from a creature pulled pretty recently from

the sea. Is the $25 lobster roll exactly the same as the one you paid 12

bucks for last summer in Point Judith? It is not. But the split, crisp,

rectangular object is as close as you are going to get on this coast.

58

Matsuhisa

(Los Angeles Times)

Nobu Matsuhisa is one of the one or two most important chefs

ever to come out of Los Angeles, not only combining izakaya cooking and

Peruvian flavors into a style that inspired chefs all around the world

but also redesigning the modern restaurant kitchen as a system running

through sushi chefs instead of the guys at the stoves. His influence is

so pervasive that we barely notice it anymore. And while the various

permutations of his up-market brand Nobu may be more luxurious,

Matsuhisa, the well-worn Beverly Hills restaurant that launched an

empire, still has all the immediacy, even if you do end up with the same

omakase menu of sashimi salad, "new-style" sashimi with garlic, uni

shooters and miso-marinated cod the restaurant has been serving for half

of forever. Matsuhisa is why a hot night out in Los Angeles involves

sushi instead of sole meuniere.

57

Guisados

(Mariah Tauger / For The Times)

Into the locavore thing? You might want to try the tacos with

chiles torreados at this Boyle Heights taquería, which is to say

ultrahot chiles grown in Armando De La Torre's backyard, sautéed until

they practically melt from the heat, served in a fresh tortilla made

from nixtamal ground several times a day in his brother's tortillería

next door. Guisados, specializing in tacos de guisados, Mexico

City-style tacos of carefully prepared stews instead of grilled meats,

is a neighborhood hangout that has become the Eastside restaurant most

likely to be visited by folks from west of the river, drawn by the tacos

stuffed with griddled shrimp with tamarind, spicy chicken tinga, or

diced pork chops in chile verde. This is one of the few taquerías in Los

Angeles where you can take a vegetarian: You'll find delicious tacos of

stewed calabacita; sautéed mushrooms with onion and cilantro; and

sizzled panela cheese.

56

Superba Snack Bar

(Ricardo DeAratanha / Los Angeles Times)

If you were to invent a restaurant whose specialties include a

cauliflower T-bone, you probably couldn't do any better than Superba

Snack Bar, an open-ended shoe box of a restaurant at the heart of

Venice's new Rose Avenue restaurant row, in a neighborhood where the

fixed-gear bicycles outnumber the Priuses. Jason Neroni's style is what

you might call abstracted Italian, which is to say that it incorporates

tastes and textures associated with Italian cooking without actually

duplicating an Italian dish. That cauliflower T-bone is a formidable

slab of the vegetable, flecked with char and smeared with a purée of

basil, citrus and olives, a Sicilian-esque preparation that is probably

as close to hedonistic as a vegan dish can get. If Superba has a

specialty, it is probably pasta: handmade, slightly stiff and leaning

toward excess, whole-wheat rigatoni more or less in the style of cacio e

pepe, cooked extremely al dente and tossed with cheese and a punishing

handful of black pepper. It doesn't quite taste like anything you'd get

in Rome. It tastes like Venice Beach.

55

Starry Kitchen

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times)

Starry Kitchen is a restaurant enriched with so many levels

of meta that it can be hard to keep straight without a scorecard. It was

founded as an occasional pop-up in chef Thi Tran and co-owner Nguyen

Tran's North Hollywood apartment courtyard before moving to a converted

fast-food place in a food court. But the restaurant seems almost settled

as a semi-permanent evening pop-up in Tiara, Fred Eric's lunch

restaurant in the Fashion District, so you can count on finding Sichuan

wontons and double-fried chicken wings, although you should probably

call a day or two in advance, especially if you want to reserve one of

the few Singapore-style chili crabs served each night. The fried rice is

made with slivers of roast pork belly and the dried-seafood components

of XO sauce, which makes the rice expensive at $15 but also an

irresistible umami bomb. Thi's pancetta-spiked take on the Vietnamese

caramelized sea bass clay pot is surpassed only by the bass heads and

tails, crisped on the grill, served with sweetened fish sauce for

dipping.

54

Tsujita

(Ricardo DeAratanha / Los Angeles Times)

Like Ginza Sushiko in the early 1990s or Rex among Italian

restaurants a decade before that, Tsujita, a spinoff of a revered Tokyo

ramen restaurant, is so far ahead of its competition that the others may

as well not exist. The broth is a complex composition of chicken, fish

and kurobuta pork; the diaphanous noodles — order them cooked hard — act

more as texture than as substance; they add little weight to the thick,

milky brew. If anything, the tsukemen, chewy noodles served plain with a

dipping sauce of greatly reduced broth, are even better, the essence of

wheat, pig and smoke. Even the simmered egg, its yolk a vivid,

reddish-yellow custard, is superb. Tsujita's biggest flaws? Lines are

long, and ramen is served only at lunch. In the evenings it becomes a

noodle-free izakaya. Thankfully, there is now an all-ramen Tsujita annex

with a slightly different menu — no tsukemen! — right across the

street.

53

Tar & Roses

(Ricardo DeAratanha / Los Angeles Times)

I am still waiting for the moment when restaurants begin to

feature wood sommeliers, dudes who come around to your table and explain

the provenance of that day's fruitwood or hickory. Maybe they could be

identified by little hatchets hanging from their necks. And if that day

ever comes, you will probably see it first at Andrew Kirschner's

small-plates restaurant Tar & Roses, where almost everything passes

through the big wood-burning oven and a line on the menu identifies the

firewood of the day. Will it be the smoky lick of almond on the singed

lettuce salad with sardines and burrata; of cherrywood on the charred

baby carrots with thickened crème fraîche and chermoula; or oak on the

roasted English peas? Is it even possible to tell which kind of logs are

involved in your next giant pork chop with greens? Tar & Roses,

which also has a terrific, mostly Italian, wine list, may also mark the

first time in our nation's history when cauliflower became more

delicious than prime steak.

52

Soban

(Soban Korean Restaurant)

When you finish describing your latest Koreatown finds to a

Korean friend, the pubs hidden away behind unmarked apartment courts,

the barbecued meat palaces and the grills specializing in exotic

invertebrates, she will always come back with the dinner she ate at her

mother's house last week — or, barring that, the restaurant dinner she

begrudgingly admits tasted a lot like something her mother might have

cooked. On such occasions, the restaurant invoked is often Soban, a

modest place on the western end of Koreatown known for the quantity and

quality of its banchan — you get 15 or so of the tiny vegetable dishes

before your entrée — but also for its compelling eun dae gu jorim,

braised cod with chile; pots of spicy braised shortribs; and especially

the like ganjang gaejang, raw blue crabs marinated in an elixir of what

seems to be a distillation of the animal's sweet juices. Alcohol is

neither served nor tolerated, setting it apart from pretty much every

other restaurant in Koreatown.

51

Picca

(Ricardo DeAratanha / Los Angeles Times)

Peruvian cuisine is one of the most captivating in the world,

a complex ballet between seafood from the chilly Humboldt Current and

the produce of the high plains; between pre-Columbian culinary

traditions, European technique and mostly Asian cooks. One can only

imagine the possibilities inherent in the choice among 50 kinds of

potatoes. Ricardo Zarate, a Peruvian chef who worked in sushi bars for

decades before breaking out with a Peruvian lunch counter near USC,

envisions Picca as an updated anticucheria, a Peruvian bar specializing

in grilled beef heart, but expanding the idea to chicken wings, sea

scallops, Santa Barbara spot prawns, even cherry tomatoes with burrata

and black mint. Zarate's conceit here is the opposite of Nobu

Matsuhisa's: Instead of inflecting Japanese small-plates cuisine with

Andean flavors, he's filtering Peruvian cooking through the aesthetics

of the izakaya, so that the meals you've been used to eating in L.A.

Peruvian restaurants become delicate, prettily arranged plates meant to

be shared.

50

Manhattan Beach Post

(Luis Sinco / Los Angeles Times)

Manhattan Beach, perhaps better known for the excellence of

its beach volleyball than for that of its kitchens, has quietly become

the restaurant center of the South Bay. For the first time perhaps since

the 1980s heyday of St. Estephe, Westsiders are heading south just to

eat. And this sprawling restaurant overseen by David LeFevre, best known

for his long term at downtown's Water Grill, is perfectly emblematic of

the modern L.A. restaurant: open kitchen, cured-meat plates, small

plates, obscure pale ales and all. The recession may be on, and everyone

is on a diet, but you'd never know it here, with people tearing into

soft hunks of braised hog jowl in fish-sauce-infused caramel, barbecued

lamb belly, and Brussels sprouts with hazelnuts. LeFevre can cook, and

he has confidence in his palate, whether it is seasoning broccoflower

with a simple squeeze of lemon and a little chile or going medieval on a

plate of sword squid with lemon curd. But whom are we kidding? You're

probably there for a crack at the impossibly rich bacon cheddar

biscuits, and I can't say that I blame you.

49

Le Comptoir

(Mariah Tauger / For The Times)

The "secret" restaurant has always been an essential

component of the Los Angeles dining scene, and if you ever managed to

make it into the unmarked steakhouse on Fairfax Avenue, the fabulous

robata hidden inside a Westside teriyaki house or the loft space housing

Wolvesmouth, you know. So when you pull into the deserted parking lot

behind a wine storage facility, climb onto the loading dock and walk

down a dark corridor into what used to be the back room of Palate, the

restaurant and wine shop that closed suddenly last year, you will

understand the aesthetic of Le Comptoir, Gary Menes' permanent pop-up: a

metal counter, a few stools and an array of portable cooking equipment

crowded into a corner of the box-strewn chamber. And you may appreciate

his cooking — simple yet evolved, based mostly on precise arrangements

of up to 20 vegetables, each separately cooked, most of them plucked

just hours earlier from Long Beach backyard farms, served to everyone in

the restaurant at the same time. His signature dish is a perfectly

fried egg with greens. There is no staff, per se, just ex-Marche cook

Menes and a single assistant cooking, serving, clearing and washing up

in front of you, then frying doughnuts for dessert. Take someone you

really like talking to. It's going to be a long night.

48

n/naka

(Glenn Koenig / Los Angeles Times)

It is almost startling to realize that n/naka may be the

first dedicated kaiseki restaurant in Los Angeles, serving expensive,

many-coursed seasonal meals, at least the first outside the Japanese

expatriate community, and that the sheer level of cooking in this modest

bungalow eclipses what you find in grand dining rooms whose chefs

appear in national magazines. The chef is Niki Nakayama, who is as

devoted to the produce from her organic garden as she is to seafood, and

it is occasionally difficult to ascertain whether the most impressive

bit of a dish is the chewy slab of Japanese halibut fin or the

thimble-sized cucumber garnishing the fish, whose texture has been

transformed into something almost luxurious through a hundred tiny

slashes of her knife. Nakayama uses lots of Western touches, but there

is a stillness to her cooking. It is fascinating how a course of fried

pompano fillets served with sautéed peppers and chips of their

deep-fried bones — you tuck them into lettuce leaves and dunk them into

bowls of sweet-sour vinegared broth — can resemble the Hong Kong-style

dish of flounder with crispy skeletons, recall the flavors of Sicilian

seaside cooking and be eaten like Korean ssam, but still seem purely

Japanese.

47

Post & Beam

(Lawrence K. Ho / Los Angeles Times)

Food-obsessed Angelenos have watched Govind Armstrong grow up

in the city's kitchens, from his beginnings as a teenage apprentice at

Spago to a run with Benjamin Ford, to his own low-key dining room at

Table 8. So his fresh take on African American dishes at Post & Beam

is new yet utterly familiar: smoked baby backs, roast salmon,

buttermilk fried chicken and greens cooked down with ham hocks with an

understated chefly flair. Plus hand-stretched pizza.

46

The Bazaar

(Lawrence K. Ho / Los Angeles Times)

There may not be a restaurant in Los Angeles that divides

foodists quite like the Bazaar, a vast, crowded hotel restaurant that is

the local vanguard of modernist cuisine. Some people think the

restaurant represents the pinnacle of José Andrés' art, that the gifted

chef is expressing something vibrant and real with his encapsulated

olives, air breads and deconstructed Spanish omelets, all inspired by

Andres' mentor Ferran Adria. Others may be happy to taste the delicious

Catalan roast-vegetable dish escalivada and first-rate Jabugo ham but

find the tricks — mozzarella balls that explode into liquid, cotton

candy mojitos, Philly cheesesteaks that too closely resemble Hot Pockets

— to be silly, especially when combined with the relative lack of

seasonal produce. But the kitchen under chef de cuisine Joshua Whigham

is admittedly first rate, able to breathe real life even into prosaic

dishes like pa'amb tomaquet, the simple length of tomato-rubbed bread

that appears with almost every meal in Catalonia. And the multiplicity

of dining spaces, including what the Jetsons might have imagined as a

dessert bar, and the ease of moving between them, may make an evening at

the Bazaar an ultimate first date.

45

Marouch

(Mariah Tauger / For The Times)

I sometimes dream of living close to Marouch, close enough

anyway to drop in at noon for grilled quail and a beer and midafternoons

for a Lebanese sweet and a thimble of thick Turkish coffee; close

enough that I didn't feel the compulsion to buzz through the mtabal,

muhammara and makanek from the mezze menu every time I stopped in so I

could order the home-style Armenian daily specials instead. The second

time you drop by Marouch, you may feel as if you live there. The third

time, you are making plans to bring all your friends. Year after year,

Serge and Sosi Brady's restaurant becomes nothing but better.

44

Din Tai Fung

(Annie Wells / Los Angeles Times)

If you get six local dumpling aficionados together to talk

about the San Gabriel Valley, you will get six different opinions about

where to go for the best Shanghai-style soup dumplings, xiao long bao.

One dude may plump for the XLB at Dean Sin World, another may prefer the

sweetish Wuxi-style dumplings at Wang Xing Ji. The old-school guy

always brings up Mama Lu's, and the woman who equates a thicker dumpling

skin with soulfulness will mention Mei Long Village, only to be

interrupted by the churl who goes for the XLB at next-door J&J

instead. But the dumpling they will all compare their favorites with,

and the place they sneak off to when they think nobody's looking, is Din

Tai Fung, the perpetually crowded outlet of a Taipei-based chain that

practically created the modern XLB cult when it opened here a decade

ago. Din Tai Fung really does have good soup dumplings, tender and

swollen with hot broth, zapped with fresh ginger, perfectly elastic and

almost engineered — you could inspect a dozen steamersful without

spotting a leak.

43

Fig

(Ann Johansson / For The Times)

If you could design a perfect chef for Los Angeles, he might

seem a lot like Ray Garcia, an Eastside guy who seems to spend almost as

much time proselytizing for healthful eating in local schools as he

does in the kitchen. At a local hog-cooking contest, he delighted the

judges by serving pozole, tamales and a pig-infused version of Mexican

squeeze candy. He has a forager on his staff, but his connection to the

nearby Santa Monica farmers market is intimate. His menu, which includes

both spinach-leaf lasagna and bacon-wrapped bacon, a salad of beets and

oranges and a plate of tongue with tomatillo, manages to be satisfying

to both the transgressive big-meat guys and the Gaia-conscious vegans;

the carb-lovers and the gluten-free. Even in this casual hotel-lobby

restaurant, Garcia cooks as if he comes from L.A.

42

The Sycamore Kitchen

(Ricardo DeAratanha / Los Angeles Times)

The Sycamore Kitchen is the breakfast-lunch project of Quinn

and Karen Hatfield, which is to say it is the sandwich-shop offshoot of a

restaurant with a Michelin star. And it turns out that obsessive

perfectionism can work pretty well in informal cafes. So a turkey

sandwich becomes almost more than a turkey sandwich, with thick slices

of nicely brined bird layered on dense house-made bread with thin

slivers of just-ripe Camembert cheese, a few leaves of arugula and a bit

of cherry mostarda. A BLT is enhanced with soft, oozing slices of

braised pork belly. And if you get there before they sell out, you

should also get the pastry called kouign amann, a.k.a. buttercup, whose

perfect caramelization requires enough sugar and expensive salted butter

to send its glycemic index screaming into the red.

41

Hatfield's

(Annie Wells / Los Angeles Times)

The rush of feverish attention paid to Karen Hatfield's

Sycamore Kitchen was surprising, in a way. Because Hatfield's, the

restaurant she runs with her chef husband, Quinn Hatfield, is one of the

quietest successes in Hollywood, a fancy place better known for the

soup shots at its bar and for stuffing yellowtail into its croque madame

than for its exquisitely seasonal vegetarian tasting menus, beef ribs

two ways or its signature date-crusted lamb. Hatfield's is the grown-up

version of what half of the restaurants in Silver Lake are trying to be.

40

Hart & the Hunter

(Ricardo DeAratanha / Los Angeles Times)

There exists, in 2013, a newish school of cooking we'll call

Ampersand Cuisine, which is to say a whimsical, vaguely ironic take on

traditional cooking often featured at restaurants that name themselves

after children's stories either real or imagined. And looked at a

certain way, the Hart & the Hunter, which is indeed named after one

of Aesop's fables, could be the restaurant equivalent of a drummerless

band in vests, the South filtered through the not-South, especially when

you are handed a plate of fried chicken skin served with a little

bottle of hand-made Tabasco, a hot biscuit with a spoonful of pimento

cheese or a steaming bowl of black-eyed peas. Is irony edible? Chefs

Kris Tominaga and Brian Dunsmoor are betting the lemon ice-box pie will

convince you that it just may be.

39

La Casita Mexicana

(Patrick T. Fallon / For The Times)

Jaime Martin del Campo and Ramiro Arvizu are the barons of

Bell, star chefs of Spanish-language media who map the produce of local

community farms onto dishes from their native Jalisco and Michoacan.

Have you ever found transcendence in a plate of chilaquiles? This is a

good place to try. La Casita is especially worth visiting during Lent

and in the season leading up to Christmas, when they prepare feasts of

the seasons' traditional foods.

38

Son of a Gun

(Mel Melcon / Los Angeles Times)

If you're a couple of Florida guys and you have a successful

meat restaurant, what you're looking for is probably a boat. Since docks

in Hollywood are hard to come by, Jon Shook and Vinny Dotolo apparently

settled for a fish restaurant you might tie a boat up to, a place with

peel-and-eat shrimp, smoked fish spread, shrimp sandwiches on white

bread and even smoked steelhead eggs with dots of maple-flavored cream

and shards of pumpernickel toast. The most popular dish? Definitely the

fried chicken sandwich, with cole slaw and what must be the only aioli

on the planet spiked with Rooster hot sauce. You could have predicted

the long communal table and the Dark and Stormys, but the uni with

burrata probably comes as a surprise.

37

Angelini Osteria

(Ricardo DeAratanha / Los Angeles Times)

Gino Angelini's mega-trattoria RivaBella may be getting most

of the attention these days, and the late La Terza probably displayed

his artistry to more obvious effect, but Hollywood has always loved his

osteria the most of all his restaurants, a place whose comfortable

versions of pan-Italian trattoria classics like saltimbocca, pollo alla

diavola, Roman tripe and his grandmother's gooey green lasagna keep the

loud dining room busy, and where whatever diet you happen to be on at

the time will be accommodated without a fuss. Some nights, it feels as

if everybody in the room knows one another, but you're in on the party

too. Some people arrange their weekly schedules around Angelini's

specials: kidney stew on Tuesdays; braised oxtails on Wednesdays, liver

alla Veneziana on Thursdays.

36

Alma

(Michael Robinson Chavez / Los Angeles Times)

Nobody has quite put a name on the new modernist school of

cooking popping up at places like Noma in Copenhagen or Coi in San

Francisco, a kind of cooking that incorporates intense locavorism, the

techniques of so-called molecular gastronomy and a sense of culinary

narrative that doesn't end when the plate is put down in front of you.

But Ari Taymor's former pop-up has the improvisatory quality of those

famous kitchens, and when you make it to the barely marked storefront,

next door to a downtown taxi-dance parlor, you never quite know what

you're going to find — seaweed-tofu beignets, perhaps, or spare

arrangements of foraged greens, or scallops with nightshade berries or

shriveled, butter-soaked carrots that somehow manage to taste better

than meat. This is a modest but sure step toward the cuisine most often

seen in restaurants with six-month waiting lists.

35

Rustic Canyon

(Los Angeles Times)

As pure an exponent of urban rustic cooking as there has ever

been on the Westside, the wine bar Rustic Canyon more or less

functioned as a restaurant arm of the Santa Monica farmers market, a

restaurant where you knew that the Persian mulberries or fat Delta

asparagus you'd been eying that morning would somehow make it onto your

plate. Under new chef Jeremy Fox, who became nationally famous as the

chef at the vegetarian restaurant Ubuntu in Napa, Rustic Canyon is still

working the farm-to-table thing but has jolted the superb produce into

something resembling a cuisine instead of some sugar snap peas on a

plate — serving that asparagus with fried pheasant egg and ultra-dense

bone-marrow gravy, pumping up a pozole with green garlic or garnishing a

profoundly black gumbo with peppery nasturtium blossoms. Fox has been

jumping from kitchen to kitchen lately. Let's hope this is the beginning

of a beautiful friendship. Zoe Nathan makes the splendid desserts.

34

Lukshon

(Ricardo DeAratanha / Los Angeles Times)

It is sometimes difficult to explain Sang Yoon to people from

out of town, who tend to see the chef as a guy who runs a successful

burger bar. "But there is bacon marmalade," you tell them, "and he won't

allow ketchup. And he started the disclaimer 'Changes and modifications

politely declined' thing," but they have already drifted off, and you

know it is only seconds before you are asked about the next cool taco

truck. But Yoon is important. The whole gastropub phenomenon stems

directly from his Father's Office. And Lukshon, his pan-Asian

restaurant, is perfected in a hundred little ways that escape the casual

observer, including the precise acidity of the sticky Chinese pork

ribs, the aromatics in the reinvented Singapore Sling and the

deconstructed shrimp toast, which he turns inside out by dredging

delicate cylinders of chopped rock shrimp in tiny croutons, then

deep-frying them to a delicate crunch. Like Roy Choi, David Chang and

Bryant Ng, he is part of a great new wave in American cooking,

American-raised Asian guys classically trained in European techniques,

veterans of the best American kitchens, who decided to re-project their

vision of American cuisine through the lens of Asian street food.

33

Kiriko

(Mel Melcon / Los Angeles Times)

Of the fine sushi bars in Los Angeles, Kiriko is perhaps the

least forbidding, a place where you know you can get perfect shirako or

sea snail in season but still treats mackerel with great respect, where

you can find all the shiso pesto and sauteed monkfish liver you care to

eat but still find a half-dozen species of silvery fish you've never

before seen. The great specialty of the restaurant is actually

cherrywood-smoked Copper River salmon with mango, a dish that certain

local sushi masters would rather die than serve. (It's their loss: The

dish is stunningly good.) And while great sushi is never cheap, Ken

Namba's traditional yet creative sushi and sashimi surpasses most of

what is sold at twice the price.

32

Vincenti

(Los Angeles Times)

Vincenti was born from the late Mauro Vincenti's Rex, the

restaurant that did more than any other to introduce Los Angeles to

Italian alta cocina. Its first chef was Gino Angelini of the famous

osteria. Its proprietor is Vincenti's widow; its chef, Nicola

Mastronardi, is a master of the big, hardwood-burning ovens, of roast

porchetta and cuttlefish salad, of the flavors of salt, clean ocean and

smoke. Vincenti is the spiritual center of Italian fine dining in Los

Angeles.

31

Shanghai No. 1 Seafood Village

(Mariah Tauger / For The Times)

The walls are covered with red velvet, and the black velvet

of the banquettes is punctuated with rhinestones. The chairs are

overstuffed. The chandeliers are blinding. If you want to be accurate

about it, Shanghai No. 1 Seafood is less a Shanghai-style restaurant

than it is an actual Shanghai restaurant, one of a small upscale chain

in the Chinese city, that just happens to have been plunked down in San

Gabriel instead of a posh shopping center in Pudong. And the

restaurant's menu, a thick, glossy document stuffed with glistening

pictures of spiked sea cucumber, is the Chinese restaurant menu

equivalent of a September Town & Country, except instead of estates,

there are red-cooked squid and live fish and fried prawns, reproduced

in excruciating detail. The cooking is not altered to suit the Western

palate, and many of its most stunning effects may whiz straight over the

heads of diners not actually raised in eastern China. So skip the

shark-lip casserole and go straight for the crabs fried with chile and

garlic; the crocks of Old Alley Pork, braised into pig candy; the smoked

fish; the stone-pot fried rice; or the pan-fried pork buns called sheng

jian bao. Cantonese-style dim sum, prepared by an entirely different

crew, is served afternoons.

30

Church and State

(Christina House / For The Times)

Before the downtown Arts District began to resemble an

open-air crane showroom, before the influx of bars and fancy

coffeehouses, Church and State was a loud artists' bistro, absinthe on

tap, strings of Christmas lights hanging all year round, that happened

to attract a pretty distinguished series of French-trained chefs. The

kitchen is home at the moment to Tony Esnault, a Ducasse veteran who won

four stars from the Los Angeles Times for his cooking at Patina, and

the bistro cooking is stunning: crisp snapper filets on a meltingly soft

bed of razor-thin confit bayaldi, braised pork belly with favas and

polenta, and a gorgeous ballotine of rabbit shocked into life with

sprigs of fresh tarragon. You can still find the tarte flambé, fried

pig's ears, bouillabaisse and roasted marrowbone with radish from the

regime of Walter Manzke, and the restaurant will never be without its

snails in garlic butter or cheesy onion soup, but the classics are if

anything even more carefully prepared. Church and State is still

probably the best bistro downtown.

29

Drago Centro

(Gina Ferazzi / Los Angeles Times)

Celestino Drago is an old-fashioned man, devoted to his

craft, devoted to the outdoors and devoted to his family, each member of

which seems to be running a restaurant somewhere in Los Angeles. Three

generations of Angelenos have grown up on his handmade pasta and his

risottos. I have never seen him happier than when he was crouched over a

long counter, dressing a flock of doves. Drago Centro, opened at the

depths of the financial crisis, is among the most majestic restaurants

downtown, a double-height dining room looking out onto the cityscape, a

view that is about command. The cooking here, led by chef de cuisine Ian

Gresik, includes both handcrafted pasta — the pappardelle with pheasant

and the handmade spaghetti with Sicilian almond pesto are wonderful —

and the meatier pleasures of steak, fish and duck.

28

Sotto

(Ricardo DeAratanha / Los Angeles Times)

Sotto is a different kind of Italian restaurant, a nominally

southern Italian place dedicated to local produce and sustainable and

artisanally produced meat, and a shrine to the awesome heat of its

15,000-pound oven. You can get the hot, fresh bread with headcheese or

puréed lardo instead of olive oil; clams cooked with fresh shell beans

and the awesomely spicy Calabrian sausage 'nduja; or a Sunday-only

porchetta practically radioactive with fennel and garlic. Chefs Steve

Samson and Zach Pollack may be pizzaioli in public, and the wood-oven

pizza is pretty good, but they really seem to be abbatoir jocks instead.

If you should happen across a special of lamb innards or one of the

gigantic sweet-sour braised pork shanks, make sure to order one the

second you sit down. Even the pastas tend to be southern things we

haven't seen locally, like the twisted noodles called here casarecce

(which means nothing more than "homemade") with a thick paste of

simmered lamb thickened with egg yolk and sheep cheese.

27

Park's BBQ

(Mariah Tauger / For The Times)

If you are keeping score at home, you can probably divide the

history of Koreatown barbecue into the era before Park's and the decade

or so since Park's opened its doors. There has always been decent

Korean barbecue in town, but the modernist Park's may have been the

first place equally devoted to aesthetics and to food, where the

fragrance of hardwood charcoal in the tabletop barbecues went into the

meat and not into your hair, where patrons sprung for ultra-prime Wagyu

beef and where the pork came from a special Japanese breed. The quality

of the galbi, the pork belly and the spicy galbi soup is superb. Park's,

distantly related to a Seoul restaurant known for its celebrity

clientele, pretty much has the top end of K-Town barbecue to itself.

26

Guelaguetza

(Barbara Davidson / Los Angeles Times)

Guelaguetza been a part of L.A. life for so long that it is

easy to forget how special it is: a serious Oaxacan restaurant serving

impeccable pre-Columbian cuisine in the heart of Koreatown, a mezcal

selection with distillates you rarely see this side of the border and a

center of Oaxacan dance where a show comes along with dinner. Hungry for

green, yellow or red mole, or chile-fried crickets? They've got those

too. At Guelaguetza, you'll find tlayudas, like bean-smeared Oaxacan

pizzas, the size of manhole covers; thick tortillas called memelas; and

delicious, mole-drenched tamales. The black mole, based on ingredients

the restaurant brings up from Oaxaca, is rich with chopped chocolate and

burnt grain, toasted chile and wave upon wave of textured spice.

25

AOC

(Anne Cusack / Los Angeles Times)

Suzanne Goin's wine bar has been an institution for so long

that it seems almost odd to drop into its new grown-up location with its

big patio, like running into a high school crush who has become a

renowned oncologist. Ordering the same old bacon-wrapped dates feels a

bit awkward. But then you settle in with a bowl of wood-oven clams with

green garlic and a glass of Sancerre, and it seems like old times. Or

Spanish fried chicken with cumin, pappardelle with nettles and

asparagus, suckling pig confit with lemongrass, and then maybe a second

glass, of Faugères, just because. Is it still hard to land a table? You

bet.

24

Salt's Cure

(Glenn Koenig / Los Angeles Times)

If you want to know whether Salt's Cure is serving the lamb

neck with mussels, which it should, always, you go over to its Twitter

feed and click on the newest link, which takes you to its Facebook page

and a picture of the current blackboard menu posted on the restaurant's

wall. It is what art critics used to call low-tech futurism. And Salt's

Cure is pretty low-tech, just a dining counter, a few tables and Zak

Walters and Chris Phelps at the range: two guys, a bar back and an

astonishing quantity of meat, charcuterie ranging from potted duck with

blueberries to the intense house-cured bacon, and a menu of simple food,

butchers' food, steaks, chops and braised animal parts; half chickens

and the occasional fish. The most popular meal at Salt's Cure is

probably the weekend brunch: smoked fish on toast, sweetly dense oatmeal

pancakes and cinnamon rolls drenched in butter.

23

Trois Mec

(Lawrence K. Ho / Los Angeles Times)

If it is 7:59 a.m. on Friday and you are an ambitious foodist

in this town, you are probably at your computer, worrying whether it is

set to precisely the right time. Because at 8 a.m. sharp, and not a

second sooner, Trois Mec releases its tables for the week, and if you

don't get through within a minute or so, you'll be sitting at the